Prior to the mayoral era, Twinsburg was run by a city manager hired by city council. This style of government worked for a while, but in the 1970’s it came time to move forward. Anthony Perici resigned from the charter commission in April of 1972 with greater political aspirations. He had been attempting to get the commission to enact a mayoral form of government where the mayor is actually in charge, eliminating the city manager. This action would make the council weaker. He resigned from the Commission to work from the outside in order to make this happen. Perici served as the president of city council from 1974 to 1976 and as part-time mayor 1977 to 1978 before becoming the city’s first full-time mayor in 1979.

The most flamboyant of all Twinsburg mayors, and city managers for that matter, Perici ruled the city with an iron fist. Often described as a dictator (in fact his nickname was “The Little Dictator”), he believed he alone could govern Twinsburg. Once when asked why he rarely visited his second home in Florida, Perici’s response was: “Who will watch the city while I am gone.”

Perici’s use (or possibly abuse) of power Perici was showcased in 1983 when he served as judge and the city council served as jury in hearings to remove Darryl Paskoff from the council for alleged neglect of duty, misconduct, and violation of his oath of office. It is unusual for the accusers to also serve as judge and jury. Perici also refused to recognize the police union. They union) took the case all the Supreme Court of Ohio.

Perici had just as many admirers as detractors. He was an old-school, hard-nosed leader and “a student of world history”, according to Adelle Nykaza, long-time city employee who worked with a number of city managers as well as the first three full-time mayors. Katherine Procop described him thusly: “He was the kind of guy you would ask to do something and boom it would be done right now.” His methods were unorthodox, but he got things done.

The second mayor of Twinsburg, and possibly the most important, James Karabec held the office for twelve years (1987-1999). For twenty-five years prior to becoming mayor, Karabec developed land and businesses for Developers Diversified. This experience, along with his time on city council and passion for the community, made him the perfect candidate. Hand-picked by his predecessor, he was far from a puppet. Perici thought he could still govern the city and that Karabec, due to his quiet nature, would oblige, but Karabec had no intention of handing the reigns back to Perici.

“I’m a great believer in giving people services,” says Karabec–a stance that differed greatly from Perici’s. Upon taking office, Karabec was told there would not be money to pay the mortgage on the sewer plant that year, but the city did have the money, and not only paid the mortgage but also improved the plant. “He [Perici] gave the services to the people, but he didn’t want to do anything extra, like build ballparks,” says the former mayor. The Karabec administration was the polar opposite; the fitness center was constructed, a golf course was bought, and property was traded to help build a new high school.

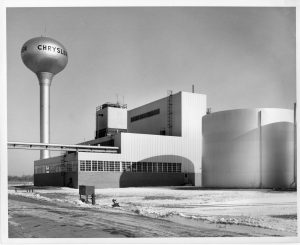

One of his greatest contributions to the city he loved was using tax abatement to bring more business into Twinsburg, helping to diversify the industrial base. If not for his foresight an initiative in recognizing the need to attract a cornucopia of commerce to the city, Twinsburg could have been set up for a huge financial hit when Chrysler departed. At one point Chrysler accounted for 75 percent of income tax revenue in Twinsburg, but by the time of the plant closing it was closer to 12 percent. The loss was devastating but far from catastrophic.

On November 2, 1999 Twinsburg elected its first female mayor, Katherine Procop. She won with relative ease over opponents, Susan D. Ferritto and William E. Hon. She would become the longest tenured mayor of Twinsburg, holding the office for sixteen successful years.

After arriving in Twinsburg with her husband and son in 1977, she almost immediately became heavily involved in the community affairs. Her first true foray into local government came in 1986, when she was appointed to the Parks and Recreation Commission, followed in 1991 by a successful run for city council. While she was on council, Karabec first suggested she become his successor.

Her greatest accomplishment may have been the procurement of Liberty Park, including the beloved Ledges, for the city. Karabec started the push for the purchase, but it was Procop who ultimately secured the land deal.

During Procop’s tenure in office there were a couple of calamities, not of her making: the demise of the Chrysler stamping plant and the tragic death of police officer Josh Miktarian. No previous mayor or city manager had dealt with such dire circumstances.

In 2009 the council and safety forces backed Procop in her quest to raise taxes a quarter percent over a four year period to offset the loss of revenue from Chrysler’s departure. Members of both the fire and police departments went directly to the voters, pushing the benefits of passing the temporary tax increase. Taxes were raised, and the loss of revenue and safety services was averted. Twinsburg residents voted to repeal the tax increase of November 2013.

When Officer Miktarian was murdered, Mayor Procop was in Maine, but merely four hours after receiving word of the tragedy she was back in Twinsburg. His death was devastating to the entire community. Procop has often singled it out as the toughest challenge of her administration and the “worst day of her life.” As tragic as this atrocity was, it brought a close-knit community even closer, aided by the leadership and compassion of its mayor.

There were other controversies that occurred during her administration, including zoning and charter issues. Though she was quite popular, there were many detractors and critics as well.A group of concerned citizens played the part of watchdog. Their criticism came from a love of the city they grew up in and a concern for the rights of the electorate.

Ted Yates was elected the fourth mayor of Twinsburg in 2015. He was born in Alabama, but in 1984 his family moved to Solon, where he finished his last two years of high school. Four years later he moved to Twinsburg.

His first foray into local government was an appointment to the Parks and Recreation Committee, serving as chairman. An avid cyclist and triathlete, he is a long-time spin instructor at the fitness center, so a position with Parks and Rec was a natural fit. In 2009 he was appointed as the Ward 3 councilman. He applied for the vacant position and was appointed by council to serve the last two years of the term. In 2011 he won an election for the same Council position.

When it became apparent to the public Procop would not run for another term, many of her supporters petitioned Yates to make a run. The move made sense since Yates and Procop shared similar visions for the city. Where they differ was Yates analytical approach to leadership honed through years of law and accounting.

Yates is focused on the creation of an “active, walkable downtown”, a critical economic driver that Twinsburg lacks. His vision is similar to what Hudson has developed on First and Main in that quaint and cozy city. Yates also sits on the board of a private, nonprofit community improvement corporation created by Procop that allows the city to acquire properties through a no-bid process. This could prove to be a useful tool in meeting Yates goals for downtown.

Only time will tell if Mayor Yates can live up to the lofty standards set by his predecessors, but all indicators point to a successful tenure.