The Township’s story began in 1817, a mere blink in of the eye from the arrival of Ohio’s first settlers. Ethan Alling, then a young man of sixteen, came to Ohio to survey family- owned land within what was then known as Millsville. Though he held countless positions in and around town over the years and his contributions to the area are without indisputable, having held countless positions in and around town, it would be the Wilcox twins, Moses and Aaron, who would eventually bestow upon the Twinsburg its current moniker. Arriving six years later, these young entrepreneurs purchased an expansive swath of land and began selling off parcels off, contributed to the creation of a school, and eventually donated a small plot of land for the creation of a town square.

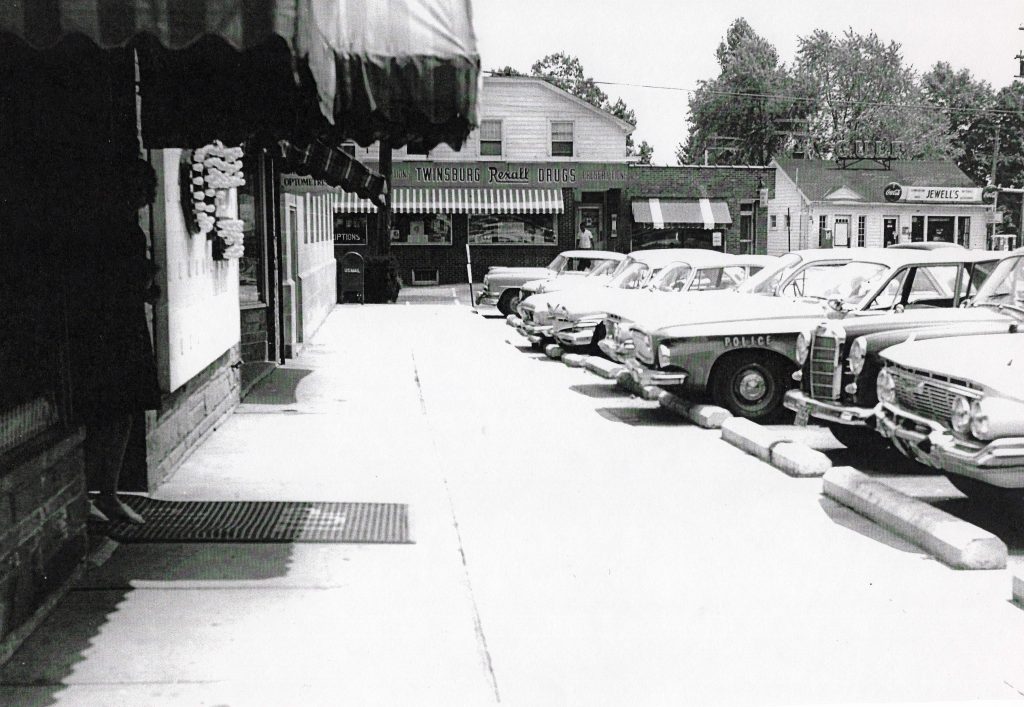

Much of the history to come would radiate outward from the this point: Twinsburg Institute, Locust Grove Cemetery, family-owned businesses, farms, school houses, and churches sprang up within view of the square. The streets lining the square, always the center of festivities. Richner Hardware, Lawson’s, and Roseberry’s appeared, providing locals with some of big-city amenities, with the comforts of small- town familiarity.

Significant growth didn’t arrive until the twentieth century. Farm and field began to give way to housing developments and commerce. Countless farms, once a familiar sight along the daily commute, began blinking out of existence. The way of life was evolving and many took note. Little could be done, however, and the transitions took place unimpeded.

During the 1920s, a man named Charles Brady saw to give African- Americans an opportunity to purchase land to form a community of their own. The newly purchased homesteads, known as Brady Homes, formed the foundation of what would become Twinsburg Heights, a tightly knit community in close proximity to the eventual site of the Chrysler stamping plant.

Chrysler would play a significant role in the area’s evolution. The formation of Twinsburg Village in 1955, separate from the Township, was sought as a means of collecting the taxes generated by the new plant, something an unincorporated township would be incapable of pursuing. So it was with that nudge that one became two, and Twinsburg and Twinsburg Township went their separate ways; Reminderville would follow suit almost immediately.

Something strange happened following the creation of these three communities, though, talks were held and attempts were made to recombine them, some as early as the 1960s. Former Twinsburg mayor Katherine Procop outlined some of the discussion:, “There were three [major] attempts, one in the ’80s and two in the ’90s, to merge the township and the city. The first two attempts were voted for by city residents but voted down by township residents. The third attempt in 1999 was finally voted for by the township residents but voted down by city residents.” Following this last attempt, the Township attempted to forge its own way, negating any future potential for reconciliation. By establishing the Joint Economic Development District with Reminderville, Twinsburg Township increased its economic stability and lessened the likelihood of future annexation talks with Twinsburg.

According to documentation supplied by Twinsburg Township,

“The Twinsburg Township-Village of Reminderville Joint Economic Development District (JEDD) is a separate political subdivision, established in 2002, per a contract between the Township and Village. The JEDD levies a 1.5% tax on employee wages and business net profits in the JEDD area, which includes all land in the Township’s industrial district. The JEDD’s primary purpose, as stipulated in the JEDD Contract and as directed by the JEDD Board, is to promote jobs and economic development in the JEDD area. The JEDD Board takes this mission seriously and, in the years since establishment of the JEDD, has overseen significant investments in the JEDD area. JEDD area investments included reconstructing and adding sidewalks and decorative street lighting to all Township roads in the JEDD area, increasing police protection for JEDD area businesses, establishing a park in walkable distance to JEDD area businesses, enhancing public transit accessibility through the addition of METRO RTA bus passenger shelters throughout the JEDD area, and clearing snow from sidewalks and bus passenger shelters throughout the JEDD area during the winter season.”

With the JEDD in place and community services secured for its residents, the Township has cleared the way for a bright and independent future. The Township began its Recreation Center Program in 2008, granting its residents access to nearby recreation centers. With police protection from the Summit County Sheriff’s Office, and fire and EMS services through the City of Twinsburg, Twinsburg Township has managed to merge the best of both city and county.